Originally published on medium

on [Unsplash](https://unsplash.com/?utm_source=unsplash&utm_medium=referral&utm_content=creditCopyText)](https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/2560/1*bxSzJy9PTvYYOtyM-VxfHQ.jpeg)

Imagine yourself going to work. You work on some kind of activity that needs computers. It’s a quiet day, everything seems okay. You arrive early, get a coffee, go to your desk and turn on your computer. Bang!

This is a “What if…” series. Here I’m gonna talk about things that developers rely on and that will cause a major setback in case of failure.

As people, we rely a lot on software. As software developers, we rely a lot on pre-built tools. Like that cool framework. Or that React lib. And let’s not forget about the servers providers. We rely on these tools. We need them. And we are all grateful for all of them and to all the people that worked to make them real.

But what if someday one of these tools glitched? Are you ready? Do you know how this glitch will take place? What will affect?

What is the thing with Timezones

If you ever developed an application that needs to be used for people in different places is likely that you ended up considering timezones. It’s also likely that you had a timezone related problem on your system. Programming time, dates, time zones, recurrent future events — this last one in special — can be a nightmare. And, as I said before, developers rely a lot on pre-built tools. So today we are going to take a deep dive into timezone and theorize about what we would do if this system crashed.

The beginning

The earth is something like a sphere that spins around itself at one revolution per 24 hours. This makes the time when the Sun appears to contact the local celestial meridian — also called noon — be different based on the longitude of your location. This time difference would not be a problem if we did not travel or communicate over long distances. It actually was what was done in the 19th century when each town and city would have their own time based on its longitude.

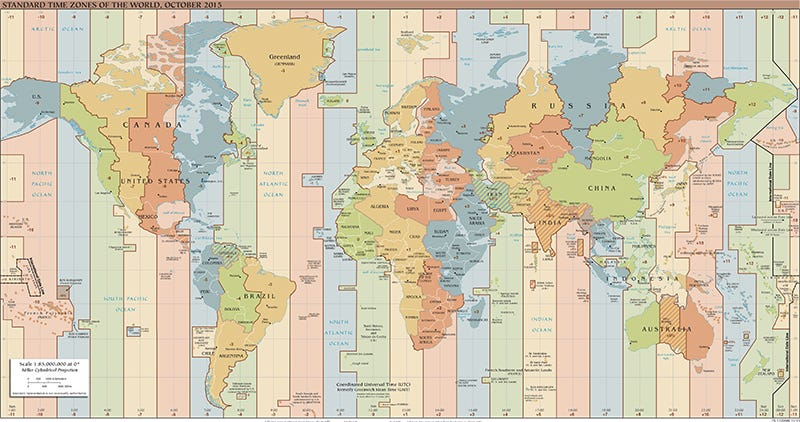

Not bad right? But things start to get really messy when we got fast long-distance travel with the railroads and instantaneous communications with the telegraph and radio. This is when time zones got created. The primary time zone, called Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), spans from 7.5 degrees east longitude to 7.5 degrees west. Then we would have only 23 other time zones with each one spanning 15 degrees longitude — right? Not quite so. Countries and territories cross these artificial boundaries because it is convenient for areas in close commercial or other communication to keep the same time.

Great. Now we can answer 2 questions: “What time it is here?” and “What time is it there?” for every place on earth. My programmer inside is saying: “24 timezones plus a map with the specifications, something I could easily code on my Python project.”

Well, there is more to it.

There’s something like 39 timezones at time of writing.

There are places with different time granularities

When timezones where created it was decided to use one hour of granularity. Today most of the time zones on land — yes, on land, because we also have nautical time zones — are offset from Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) by a whole number of hours (UTC−12 to UTC+14) like originally intended. However, a few zones are offset minutes of 30 or 45 minutes, some examples are Newfoundland Standard Time UTC−03:30, Nepal Standard Time UTC+05:45, and Indian Standard Time UTC+05:30.

There are places that adopt daylight saving time

The idea of daylight saving is that people should go outside during sunny evening hours, decreasing the electricity used at home and saving energy. Germany was the first country to implement a daylight saving program, which it did in World War I, in an attempt to conserve energy for the war effort. Shifting the clocks by one hour during the summer to save energy, results in not being able to determine local time based only on location. The result is if you have to use a time in the past it is mandatory to know if daylight saving time was in effect. There is also, a particularly complex situation that occurs twice a year in time zones that use daylight saving time. In the spring when the daylight saving time (DST) takes effect, there is an hour in local time that does not exist and a day that is only 23 hours long. In the fall the opposite happens — a whole hour occurs twice in the same day and that day is 25 hours long. This is just great for your time-related system that has a recurrent task for every 4 hours.

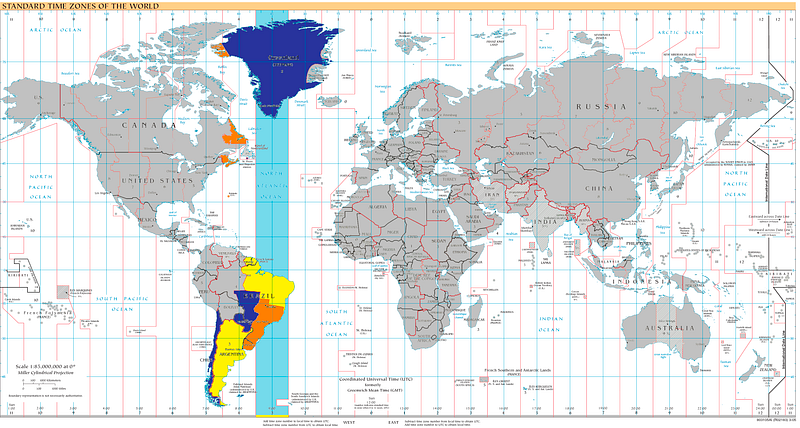

All these complications might sound bad enough to deal with, but don’t worry, the reality is even worse. There are States and Provinces that do not use Daylight Saving Time. For example, in Brazil, the Northeast and North regions do not adopt DST time, while the rest of the country shift their clocks on hour forward. On the USA there’s even a more bizarre example: Arizona and Saskatchewan don’t follow the DST, but the Native American Reservations inside Arizona do use DST.

There is Samoa

Samoa is a country consisting of two main islands Savai’i and Upolu with a few smaller islands around. Located right at the east of the International Date Line, but it used to actually follow the dateline accordingly. The International Date Line (IDL) is an imaginary line on Earth’s surface that defines the boundary between one day and the next. In the years before 2011, Samoa went:

“Hey, most of our major trading partners — China, Australia, New Zealand — are on the other side of the dateline, so when we’re working away at the office on Friday, the rest of the people we actually do business with are already out for the weekend”.

Samoa decided to change timezones to line up better economically, so on December 29, they went straight to December 31, skipping the full day of December 30. Another similar thing happened on 4 July 1892, when they did the exact same time only mirrored. They looked around and said:

“Hey, our major trading partner is the United States, why are we in a totally different day?”

So they did July 4, 1892, twice. That’s history my friends — great icebreaker in my opinion.

And there are edge cases: is February 30 really a fictitious date?

If you code a program to be used in Sweden and has some kind of historical context you would have to consider that February 30 was a real date on 1712. Very complicated story, that ends with some people losing 11 days of their lives.

Timezone problems are political.

They get added gradually, over time, depending on political whims, geographical reality, and economic plausibility. On Brasil 2018, the start of the DST was delayed by a presidential law. The nation was in the middle of the electoral process and the voting machines — unique voting process on the country — could not support having different turns of the same election in different timezones. So, the president sanctioned a law to change the start date of the daylight savings, this change was “widely” advertised and still, some telecommunication companies shifted smartphones clocks to DST time. This is one of the crazy problems caused by timezones.

To solve these problems: TZ Database

Some great people put together a compilation of information about the world’s time zones to use with computer programs and operating systems: the tz database (also known as the Olson database). Which is the listing of timezone rules, daylight savings transitions, and unexpected timezones changes and gets updated a lot of times a year. For Python, there’s the pytz library, allowing accurate and cross platform timezone calculations. Every language should have their own timezone library/module that under the table is using the latest version of the Olson database.

Timezones in practice

Let’s analyze 3 scenarios of timezones problems, each one with a different intensity level: Light, Urgent and Nuclear. Imagine yourself going to work. It’s a quiet day, everything seems okay. You get a coffee, go to your desk and turn on your computer (you’re a software developer). Your mailbox is clean, but your slack channel is buzzing with a strange bug report.

Light Scenario

You work for a signature system. People pay some money to receive something in their houses with a certain periodicity. The client you work for only deliver products on Fridays. Back to your desk, you have a strange bug report. Some customer is complaining about seeing the date of the delivery as a Thursday. The investigation begins. You go to the customer’s account and see that the date is in fact wrong. The system doesn’t allow delivery dates on days that are not Friday, is this bug making the system allow these situations? You decide to make a simple query to see what is being saved.

Suppose you are using a Postgres database. Timestamps with time zones are always stored in UTC (Universal Coordinated Time, traditionally known as Greenwich Mean Time, GMT). An input value that has an explicit time zone is converted to UTC using the appropriate offset for that time zone. If no time zone is stated in the input string, then it is assumed to be in the time zone indicated by the system’s TimeZone parameter and is converted to UTC using the offset for the timezone zone.

2018–12–21 00:00:00–03

These numbers are in UTC and using the ISO 8601 that defines the order: year (YYYY), month (MM), day (DD), hours (HH), minutes (mm), seconds (ss) and time zone offset (Z or +hh:mm or -hh:mm). The date is being saved on UTC-3 which can correspond to any one of these places:

One important thing about this date is the time, is set to midnight, which means that any place with a west timezone will see the delivery date one day early. That’s our bug, users seeing the delivery date one day early. The solution to this problem is very simple, just present the delivery date on the system default timezone. All system have limitations and all system make assumptions. This is not a bad thing, this means that the developers, the client and the users must be aware of these limitations and assumptions.

It’s a simple problem, with a simple solution, unlikely to happen, but check who also had the same problem:

Urgent Scenario

Continuing with the idea of a signature system, suppose you want to send an email three days after the delivery to ask for some feedback. Simple task right? For this scenario, we will use the New York City time.

import pytz

from datetime import datetime, timedelta

NYC = pytz.timezone('America/New_York')

dt = datetime(2018, 11, 2, 0, tzinfo=NYC)

print(dt)

# 2018-11-02 00:00:00-04:56

Odd! New York regular timezone is UTC-04:00 from when this 04:56 came from? This problem is related to the Python implementation, the NYC timezone is being blindly attached to the DateTime object, without analyzing its year, month, etc. Since the date is not known, it ‘s impossible to determine what was the time legislation at the moment, so it is assumed that you just want the geographical time for New York. Why did pytz return that? Because that was the local solar mean time in New York before standardized time zones were adopted, and is thus the first entry in the America/New_York time zone. To easily solve this:

dt = NYC.localize(datetime(2018, 11, 2, 0))

# 2018-11-02 00:00:00-04:00

Now, let’s get the date to send the feedback email:

dt_to_send_email = dt + timedelta(days=3)

# 2018-11-05 00:00:00-04:00

print(NYC.normalize(dt_to_send_email))

# 2018-11-04 23:00:00-05:00

November 4th was the end of the DST, so at 2 AM clocks were turned

backward 1 hour to 4 November 2018, 01:00:00. Because of the timezone

change on the period of the date operation, it’s imperative the use of

the normalize{.markup–code .markup–p-code}function, to set the new

date according to the new timezone. This one hour difference between the

dates may not look a serious problem to our feedback email task, but can

be a really big deal for calendars. Imagine being late for all your

meetings every time that the timezone changes and you can see the

dimension of the problem.

Nuclear Scenario

If you ever worked with Python and had the need for a distributed task queue is likely that you end up using Celery. One of the features available is a scheduler, that kicks off tasks at regular intervals to be executed by available worker nodes in the cluster. Imagine yourself using this library, to schedule very critical tasks to your application. The day and the time for these applications to run is crucial, you need to run them every Monday at noon.

The periodic task schedules use the UTC timezone by default, but you can

change the timezone used using the timezone{.markup–code

.markup–p-code} setting.

timezone = 'America/New_York'

Now, you use the celery beat scheduler to define this very important task:

from celery.schedules import crontab

CELERYBEAT_SCHEDULE = {

'very_important_task': {

'schedule': crontab(hour=12, minute=0, day_of_week='monday'),

'task': 'myproject.tasks.very_important_task'

},

}

Great! Everything is working and remains this way for years. However, someday you update Celery to a new version, and suddenly your tasks start to run 5 hours yearly.

Apparently, your tasks are running in UTC now.

This actually happened to me, was a crazy day. Once we realized that the tasks were running in UTC the solution was very straightforward, just change the time of the tasks to UTC:

from celery.schedules import crontab

CELERYBEAT_SCHEDULE = {

'very_important_task': {

'schedule': crontab(hour=17, minute=0, day_of_week='monday'),

'task': 'myproject.tasks.very_important_task'

},

}

This issue was already solved by a celery update, details to this issue here.

What if the timezone system crashed

From the previous examples, we saw that timezones itself can cause a lot of problems if your code is not prepared to deal with it changes and even if the code is fully prepared some library you use can launch a new version and break everything on the blink of an eye. Let’s face it, if somehow the Olson database is corrupted or deleted or by any means stop being updated there would be very little we can do.

Concluding, the world is not ready to go on without timezones, and big thanks to everyone who works to make sure we don’t have to find out.